Journal of Urban Health 2020 (in press)

Journal of Urban Health 2020 (in press)

A Community Responds to the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study in Protecting the Health and Human Rights of People Who Use Drugs

Robert Heimer1

Ryan McNeil2

David Vlahov3.

1. Department of Epidemiology of Microbial Diseases and the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, Yale University School of Public Health, New Haven, CT

2. Yale Program on Addiction Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

3. Yale University School of Nursing, West Haven, CT

Running title: COVID-19 Protections for People Who Use Drugs.

Word Count

Text:4,332

Abstract: 185

Key Words: People who use drugs; COVID-19; Harm reduction; substance abuse disorders; \ treatment for opioid use disorders; homelessness; incarceration;

ABSTRACT

Effective responses to a global pandemic require local action. In the face of a pandemic or similar emergencies, communities of people who use drugs face risks that result from their ongoing drug use, reduced ability to secure treatment for drug use and correlated maladies, lack of access to preventive hygiene, and the realities of homelessness, street-level policing, and criminal justice involvement. Herein, we document the efforts of a coalition of people who use drugs, advocates, service providers, and academics to implement solutions to reduce these risks at a municipal and state level focusing on New Haven and the State of Connecticut. This coalition identified the communities at risk: active users needing access to harm reduction services, persons in treatment needing access to their medications, the homeless and marginally housed needing improved hygiene, people engaged in sex work, and the incarcerated needing release from custody. The section describing each of the risks demonstrates how the coalition acted preemptively at early stages of the pandemic, ahead of official initiatives, to develop ameliorative risk reduction solutions. Outcomes discussed include instances in which obstacles were overcome or still remain.

Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic has spread with catastrophic rapidity, the identification of high-risk populations has focused on the elderly, people with pre-existing somatic health conditions, and, more recently, people living in poverty and people of color. Under-appreciated in this discussion has been the heightened risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 virus among people marginalized by substance use, homelessness, and housing instability. There are approximately 20 million Americans with substance use disorders (SUD), while as many as half a million people are homeless on any given night.1,2There have been some efforts by government agencies to increase the awareness of the vulnerability of these populations, including from the Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.3Guidance from federal agencies to service organizations working with people who use drugs (PWUD) and people who are homeless have emerged slowly, but lack specifics particular to the difficulties faced by these populations.4,5To address the gaps in government recommendations, public health researchers and advocates have produced prescriptive or aspirational white papers, scholarly manuscripts, and inspirational briefings suggesting necessary steps to protect these populations, with attention to differences across gender, race, and place.6-8These efforts have, at the local level in the U.S., begun to change policies concerning PWUD, their access to services, and their interactions with the criminal justice and correctional systems.9

The pandemic has overshadowed but not ameliorated the existing opioid crisis, which continues even as PWUD become infected with SAR-CoV-2. Epidemic control measures such as social distancing and the shuttering of non-essential services may be detrimental to the health and well-being of PWUD, who are seeking treatment for problematic drug use, who are already in treatment, or who are homeless or incarcerated. These efforts may heighten overdose risk by pushing people to inject alone and undermining access to syringe exchange, naloxone distribution, and outreach support services. People in abstinence-based recovery have experienced disruptions as treatment programs and fellowship meetings central to their well-being have been shuttered.10-13COVID-19 outbreaks in jails and prisons have killed incarcerated persons and guards alike. Up to three-quarters of incarcerated persons in one Ohio facility and throughout the federal prison system have tested positive.14-16Those without shelter are faring no better now under threat from COVID-19 than they fared prior to the threat.

While all of the adverse consequences of COVID-19 among PWUD are noted at a nationwide level, it is important to report where local efforts to manage the impact of COVID-19 in these neglected populations are being pursued and succeeding. New Haven and Connecticut are appropriate venues for documenting efforts and partnerships as a first step in determining if they have formed the basis for reducing morbidity and mortality among PWUD. The city and state were bellwethers for the expansion of syringe exchange programs thirty years ago, presenting the first biological evidence for the effectiveness of such programs in slowing HIV transmission rates among people who inject drugs.17-19Connecticut is also an exemplar of how the expansion of such programs along with easing of syringe access prohibitions and expanding effective antiretroviral treatment, have successfully reduced new HIV infections attributable to unsafe injection to an average of 25 newly diagnosed cases annually in the past decade from highs of 750 new AIDS diagnoses per year in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The state has also seen efforts to respond to the more recent opioid overdose crisis. Statewide efforts led by the same harm reduction community that overcame the HIV epidemic have expanded community training in and distribution of naloxone and mobile prescribing of buprenorphine. Connecticut addiction treatment professionals have pioneered efforts to expand evidence-based treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD). New Haven researchers working at Yale have championed buprenorphine treatment in out-patient medical practices and emergency departments.20,21Opioid treatment programs, most notably the APT Foundation in New Haven, have expanded evidence-based treatment for OUD by adopting open access models that eliminate waiting lists and shorten intake times to 90 minutes.22Methadone treatment has been expanded to incarcerated persons in six of the state’s correctional facilities, beginning with the jails in New Haven in 2013 and in Bridgeport the following spring.23Treatment in correctional facilities has been complemented by efforts of the Department of Corrections, which have reduced the incarcerated census by one-third between 2010 and 2019.24

Unfortunately, despite all the positive policies and practices, implementation of the state’s opioid response plan has been hampered by diminishing funding as government revenues have been slow to rebound from the 2008-09 recession. Opioid-involved fatalities in Connecticut exceeded 1,000 in each of the last three years, yielding a state-wide overdose mortality rate around 30/100,000. Despite falling incarceration rates, 40% of all opioid overdose deaths continue to occur among people with a history of incarceration in the state’s correctional facilities.

SAR-CoV-2 entered this environment in early 2020, with the first cases appearing in the wealthiest part of the state, suburban Fairfield County, in early March and spreading inexorably north and east since. We document efforts, in response to this spread, that seek to protect the vulnerable populations described above.

Methods

A case study approach was taken to document local and statewide efforts to identify and address pre-existing policies and practices to prevent COVID-19 infection and mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic among overlapping population centering on PWUD in New Haven and more broadly Connecticut: those with SUD, the homeless and marginally housed, and the incarcerated. Given that SUD are chronic, relapsing conditions, our focus includes active users and those in remission whether in treatment or trying to remain abstinent. We detail steps taken to identify and remedy problems created by policies or practices that preceded or were instituted in response to the COVID-19 spread. We provide a chronology of problem identification, proposal for its solution, and outcomes in terms of improved policies and practices.

In documenting the problems and responses, we emphasize the increasing prevention measures for each group by collecting accounts from service agencies, local and national news sources, meeting notes, and personal experiences. In the first section of the findings, we present data on the size of the three vulnerable populations and the overlap between them using data from governmental agencies and non-governmental organizations that have conducted actual counts or have attempted to estimate the size of hidden populations. Censuses collected by the Connecticut Department of Correction (CT-DoC) and the Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness (CCEH) provided numbers of incarcerated and homeless populations, respectively. Data on the number of people receiving treatment for SUD were obtained from annual reports of the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DHMAS) that cover the programs operated or funded by the agency. Number of unduplicated individuals are divided into those receiving agonist-based treatments – methadone and buprenorphine – at opioid treatment programs and those who received some form of facility-based abstinence-based treatment – in-patient detoxification or out-patient rehabilitation.

COVID-19 prevention efforts for the populations are presented alongside dates of significant COVID-19 events to demonstrate the proactive nature of many of the efforts. Documentation of the efforts at the local and state level include advisory bulletins to drug using populations and advocacy efforts to change policies deemed ineffective, counterproductive, or civil and human rights violations.

Local and state newspapers, broadcast media, and news aggregators and government websites comprise the sources for publicly available information pertinent to the populations of concern in this report. These sources were searched online. Sources for decisions by PWUD and those in treatment, advocates for these populations, and allies from intersectional advocacy communities include the contents of messages alerting members of the advocacy community initiative, meetings, policy briefings, interactions with police, public officials, etc. Reports from frontline providers include the contents of messages alerting members of community initiatives, meetings, policy briefings, communication with police or public officials. Outcomes are mostly descriptive; at this stage it is premature to ascertain impacts in either health or economic terms. More quantitative analyses must await future investigations once more outcomes data become available.

Findings

The first confirmed COVID-19 case and death in Connecticut were announced on March 3 and March 21, respectively. Beginning on March 10, the same day that Connecticut’s Governor Ned Lamontdeclared a civil preparedness and public health emergency,the local harm reduction working group based in New Haven met to address the pandemic’s impact on local intersecting populations whose past or present drug use could place them in harm’s way. The New Haven Harm Reduction Working Group (NHHRWG) is an ad hocgroup of academics, community advocates, PWUD activists, and healthcare and service providers facilitated by faculty from the Yale Program in Addiction Medicine and the Yale Global Health Justice Partnership of the Law School and School of Public Health. As cases of COVID-19 in Connecticut mounted and the need for immediate action increased, meeting went from biweekly face-to-face to weekly Zoom videoconferencing.

Estimating the Size of the At-Risk Populations

An important chore has been to identify or estimate the number of people in each of the overlapping groups. PWUD fall into three non-exclusive categories: those in medicalized treatment, those pursuing abstinence without treatment, and those actively using. Treatment programs supported by the state report the number of people served to DMHAS. In 2019, the state recorded 29,416 with opioid use disorder in treatment of whom 14,088 were receiving medications through treatment programs. An additional 31,433 people with SUDs including OUD received abstinence-based treatment through these programs. These numbers, however, present a limited picture of the size of the PWUD population. This estimate will not include those pursuing abstinence on their own or through 12-step approaches, those receiving buprenorphine-based treatment for OUD if prescribed outside of an opioid treatment program, or those who sought no treatment. It is estimated that 20-25% of those incarcerated in Connecticut’s unitary correctional system of 4 jails and 15 prisons have a SUD. Although the prison population has been reduced by one-third since 2010, there were still 12,381 people in DoC custody as of January 1, 2020. CCEH conducts a point-in-time count in late January that includes sheltered and non-sheltered individuals and families, which are stable overall but vary more widely for the unsheltered individuals. Their 2019 count found 3,033 homeless individuals statewide and 503 in New Haven. In the subset of unsheltered homeless, the count found 503 individuals statewide and 80 in New Haven. Advocates serving the homeless believe that the number of unsheltered individuals is 50-60% higher than the count.

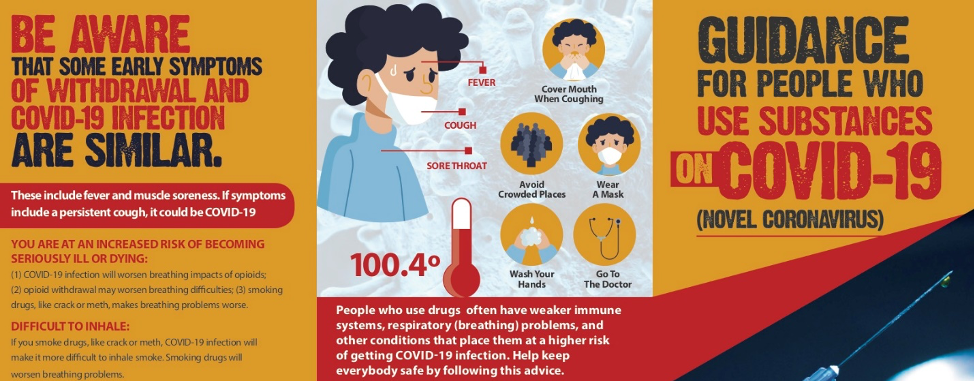

The working group initiated an active response to the threat of COVID-19 by undertaking efforts to inform and protect at-risk populations. For people actively using drugs and in treatment, the group adapted guidance documents on coronavirus protection from other sources to local conditions. Within a week, the group had produced an adapted guidance document through the use of Google Docs for shared text editing.25The comprehensive advice for people actively usingopioids, psychostimulants, and alcohol covered (1) SAR-CoV-2 infection symptoms and how these compare to symptoms of withdrawal; (2) information on how the virus infection could complicate drug administration, especially for those who smoke their drugs; (3) considerations on how to manage to possible scarcity of drug supplies and naloxone to reverse opioid overdoses, and (4) how to manage scarcity of disinfectants to clean drug paraphernalia. For people prescribed medications for OUD, the bulletin advised clients that while continuing on medication might prove stressful, they should remain physically distant but socially connected with their medical providers, e.g., through telemedicine, and seek to increase the number of take-home doses dispensed at any one time. Working with collaborators in other parts of the state, brochures in English and Spanish were created, printed in color, and distributed to harm reduction and syringe service organizations throughout the state (Figure 1). The guidance document and brochure also have been widely disseminated online on Twitter and Facebook and by regional, national, and international harm reduction organizations, and through an international webinar organized by the International Society for Addiction Medicine, and Crackdown,26an award-winning and drug user-led podcast that reaches a broad national and international audience.

SAMHSA issued its first guidance document for the delivery of medication to treat OUD on March 16, the same day schools in Connecticut were closed statewide.27,28The Yale Program inAddiction Medicine developed and disseminated comprehensive guidance thatwent beyond those from SAMHSA. These highlighted the benefits of lifting many of the burdensome mandates. In addition to increases the number of doses provided per visit to clinics (for methadone) or pharmacies (for buprenorphine), providers were notified that where clinically indicated they could reduce or eliminate for the short run urine toxicology screens and face-to-face counseling sessions that unnecessarily expose patients and service providers to SARS-COV-2. The guidance also called for some systematic changes including a greater reliance on telemedicine, home delivery of medications, back-up medical coverage and IT support in case providers become stricken with COVID-19. Importantly, the safety and efficacy of the induction of methadone treatment for hospitalized patients with OUD was sanctioned. Broader recommendations, with a focus on expanding access to buprenorphine have been published by Program faculty.29

In the New Haven area, the majority of people in medication-based treatment for OUD rely on the APT Foundation. APT had 4,542 patients receiving methadone on March 16 when the leadership met and agreed on procedural changes. All 2,009 patients already receiving at least 5 days of take-home doses were to receive a 28-day supply. Those with 4 doses had their take-homes increased to 14 days. These changes reduced traffic flow at the clinic sites by more than half. All those with daily doses were increased to alternate days. As of May 5, just 287 people (6.3%) were receiving doses daily, with about 25% of them newly admitted since March 15.

On Monday, March 23 Governor Lamont, joining governors from New York, New Jersey, and Illinois, ordered people to stay home as much as possible and issued new regulations aimed at keeping only essential business functioning.30Homeless, marginally housed, and street-involved persons, including PWUD and sex workers, are adversely affected by the these necessary epidemic control measures. Reaching them in public spaces and offering face-to-face assistance became challenging and accommodations needed to be found for those who might test positive. In New London, the homeless get support from the Homeless Hospitality Center – a facility not equipped to provide spaces to isolate the infected and quarantine the exposed. Although the Center generally applied strict rules about on-premise drug use, it opened discussions about creating spaces for separation and relaxed policies on March 17, ten days prior to New London’s first diagnosed COVID-19 case. The ensuing discussion injected the principles of harm reduction into a homeless service agency previously basing policies on abstinence. The agency identified and instituted measures ensuring that affected individuals served by the Center were less likely to violate isolation or quarantine and expose others to infection without suffering through drug withdrawal, implementing a policy adopting a don’t ask, don’t tell approach. As the burden threatened to grow too large for space at the Center, the city’s social service director and the fire department arranged to use an unoccupied building that formerly housed a nursing care facility.

In New Haven, the conversion of a closed high into a respite facility for homeless PWUD upon discharge from the hospital was challenged by local opposition that included a neighborhood elected official. Resolution allowing its opening required intercession by the newly inaugurated mayor.31Thereafter, allowing the facility to operate on harm reduction principles required negotiations with city officials. The principles have been codified in an operating protocol prepared by physicians from the West Haven VA’s homeless program, Yale’s National Clinical Scholars Program, and homeless advocates including the former director the city’s largest shelter. This protocol has been highlighted as a national model by the National Coalition for the Homeless and is featured prominently on their website.32The protocol includes tolerance for alcohol and drug use and providing an outdoor space for smoking, while providing comfortable accommodations that has encouraged patients to remain until longer-term housing became available. An early barrier overcome at the respite shelter was arranging for methadone, prescribed for OUD while a patient was hospital, to be delivered to the respite facility. Intercession by faculty from the Yale Program in Addiction Medicine and cooperation with the APT Foundation to ensure daily dosing ensured adherence to the respite’s harm reduction mission. The shelter has operated with a census between four and eight people recovering from COVID-19, and people fully recovered from their COVID-19 infection have been moved to one of four local hotels contracted by the City of New Haven to provided transitional housing.

A consideration when addressing the homeless outside of the healthcare and respite system has been the closure of buildings, such as public libraries and interiors of fast food restaurants, where people used restrooms and washed their hands to minimize virus transmission. Loss of these spaces removed locations where PWUD had congregated, hampering the ability of street outreach teams to distribute harm reduction supplies and provide medical care. Negotiations by the NHHRWG with city officials have slowly led to installation of sanitary facilities including portable lavatories and hand washing stations. Placement of facilities has not always been in places where the homeless habitually congregate, and the advocates have repeatedly requested relocation to more appropriate locations and reduced police surveillance of these sites. Efforts to add syringe disposal drop boxes to the portable lavatories remains a challenge.

The NHHRWG, through multiple letters signed by public health and legal experts and advocates, has sought to nudge New Haven local government to change policing practices in relation to drug use through the non-enforcement of non-violent, victimless crimes, non-harassment of harm reduction outreach workers and the communities they serve, and improved mechanisms for complaints and accountability. The effort has produced little response, complicated, in part, by the recent failure of a law enforcement diversion program in the city that yielded only two successful arrest diversions in 233 arrests over a six-month pilot period.3334Police officers with a criminal justice orientation have continued to harass people who use drugs, sex workers, and the homeless and interfere with the outreach workers who provide critical services to these individuals. Despite reassurances from the police chief, the mayor, and the director of social services that interference is not official policy, little has been done to rein in aggressive policing. While the mayor, in a private communication with one of the authors has indicated that changes have been made to policing practices due to the pandemic, specific information regarding these changes has not been made publicly available despite repeated requests, and local harm reduction providers have continued to report police interference in their activities.

The incarcerated, especially those with histories of drug use, remain vulnerable to COVID-19. In Connecticut, the first two confirmed cases in the state’s correctional system were reported on March 29. At that time, the total incarcerated population was 12,459. Within two weeks the first incarcerated person had died from the virus and by the beginning of the following week, almost 300 prisoners had tested positive, and more than half of the healthcare workers at the first facility reporting cases were infected or under quarantine.35The correctional population has decreased by nearly 1,500 as of May 1, to slightly less than 11,000 through routine discretionary and scheduled end-of-sentence releases.24However, the infection rate for persons incarcerated within the Connecticut correctional system as of April 20, 2020 was more than 250 per 10,000, 5.2-fold higher than the statewide prevalence. The response by a coalition of correctional reform and harm reduction groups was drive-by, “honkathon” protests, past the gates of correctional facilities and two at the governor’s mansion in Hartford. Meanwhile, two civil suits have been filed on behalf of prisoners by the American Civil Liberties Union.36The first suit was dismissed in late April.37The more recent one seeks release of prisoners at the higher risk of serious sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection – those aged 50 or older and those younger with serious existing conditions. Further efforts have had minimal impact in reducing density; continued viral transmission among incarcerated persons and correctional staff is likely. Longer-term efforts to reorganize and improve the housing situation for people being released from custody, with necessary financing, appears to be moving forward but faces an uncertain timeline.38Meanwhile, the slow trickle of releases continues, as does the increase in infections among those in custody with no public responses or assurances that the rate of release will increase soon enough to prevent further deaths.

On April 23, Governor Lamont announced the formation of a committee charged with providing guidance on reopening the state.39The NHHRWG has proactively prepared a memorandum addressed to this group detailing steps to ensure that drug using populations will be protected. Five major actions were identified: (1) ensuring that organizations serving these populations and their staffs be classified as essential thereby increasing their financial stability; (2) ensuring that the staff are guaranteed personal protective gear, (3) maintaining public hygiene facilities including toilets and hand-washing stations in easily accessible locations, (4) increasing efforts to reduce police harassment and civil right violations, and (5) designing COVID-19 testing options that allow access for individuals without stable residences or transportation options. As progress is made towards reopening Connecticut, the harm reduction community will continue to monitor the extent to which these steps are taken.

Discussion

The primary public health response of physical and social distancing created, perhaps paradoxically, an opportunity to examine standing policies and practices that would threaten the health of these vulnerable groups. Central to these responses has been an insistence upon providing appropriate levels of social distance protection, SARS-CoV-2 infection testing, and treatment. The urgency of responding to the pandemic has also focused attention on improving the conditions that tend to worsen the course of the disease: SUD, homelessness, and incarceration.

In addition to creating safe distance access to drug treatment programs, there have also been steps to reduce the onerous restrictions that have caused clustering of patients around clinical sites that offer methadone treatment. Much of the not-in-my-backyard opposition to these clinics revolves around such clustering. One positive longer-term outcome would be maintaining the increased take-home doses and hence the time between mandated clinic visits. This will benefit patients, reducing the time spent travelling to clinics, but also providers and clinics by reducing patient volume and expanding capacity to manage more difficult patients. It may even reduce the stigma clinics face if the volume of patient traffic is decreased. While the changes in regulation promulgated by SAMHSA are temporary, advocates and academics will need to marshal evidence during the period of programmatic flexibility to make the temporary changes permanent.

Local efforts described here have led to improvement in the street amenities available to the homeless and in the effective provision of supportive housing options. At this date, the supportive housing situation in New Haven and New London has been resolved through respite facilities that transfer recovered homeless individuals to municipally supported housing. The respite facilities have incorporated elements of harm reduction principles in their operating protocols. It will become an important point for future discussions to determine the extent to which such facilities would be amenable to embracing a stronger harm reduction role as safer consumption spaces. The NHHRWG is likely to take a leading role in facilitating such consideration. Unfortunately, the NHHRWG has not been as successful in making sure that accessible public hygiene facilities are deployed. More work needs to be done to ensure that hygiene and housing are provided where needed and that such housing meets the needs of PWUD. The pandemic has shined a harsh light on failures to attend to these needs, and to the negative role of policing. Continued activism will be needed to protect the rights of the homeless and create a more integrated system to attend to their needs. Working together in New Haven and at the state level has fostered an increasing commitment to and new coalitions for this activism, which will be necessary to maintain pressure on local and state authorities to retain newly installed facilities and upgrade housing options. Likewise, violations of the civil liberties by over-zealous police officers will need to be addressed as an ongoing issue. On a more optimistic note, the city has accepted harm reduction as the guiding principle for respite housing and has obtained a large grant that will allow hiring a harm reduction coordinator for the city. This commitment can concentrate efforts on policies and actual practices that reduce tension between police and at-risk communities.

The complicated issue of decarceration remains unsettled. The governor and the Department of Correction appear content with continuing the slow pace of the declining incarcerated population at about 800 per month. There has been no official response to the repeated calls and court actions by the coalition of civil rights, decarceration, public health, and harm reduction advocates to more quickly release or move incarcerated persons to lower security facilities. The continuing increase in their COVID-19 prevalence is a testament to the failure to more rapidly release prisoners and the poor implementation of the existing isolation and quarantine plans. The one improvement is a commitment to universal testing within the correctional system, but this is not likely to be completed until the end of June 2020.40

The benefits of having in place a community-academic harm reduction partnership such as the NHHRWG have become apparent as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded locally. It mobilized prompt attention to emerging community needs. University partners have added legal and public health rationales to drug user and advocates place- and time-specific calls to action. Inclusion of healthcare and social service providers in the working group has added the ability to address individual needs while working in the larger context of promoting societal change to improve the lives of PWUD and those experiencing the negative criminal justice and housing consequence of their drug use. The approaches taken by the NHHRWG are illustrative of the power of intersectional action and can help guide how others proceed when facing emergent health emergencies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following members of the harm reduction community who participated in the activities described in this report, provided working papers and draft materials, and reviewed the final draft for accuracy. Special thanks to Poonam Daryani, Gregg Gonsalves, Lynn Madden, Alice Miller, David Rosenthal, Evan Serio, and Kelly Thompson.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Citations

1. National Alliance to End Homelessness. The State of Homelessness in America. 2017: Washington, DC. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-report-legacy/. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

2. National Survey of Drug Use and Health. National Insititute on Drug Abuse; 2019: Rockville, MD. https://www.drugabuse.gov/national-survey-drug-use-health. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

3. Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and Addiction Epidemics. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020; published on-line. doi:10.7326/M20-1212.

4. National Institute on Drug Abuse. COVID-19: Potential Implications for Individuals with Substance Use Disorders. National Insititute on Drug Abuse. 2020: Rockville, MD. https://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2020/04/covid-19-potenti…. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Guidance for Homeless Service Providers to Plan and Respond to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020: Atlanta, GA. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/homeless-shelters/pl…. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

6. Akiyama MJ, Spaulding AC, Rich JD. Flattening the Curve for Incarcerated Populations — Covid-19 in Jails and Prisons New England Journal of Medicine. 2020; published on-line, doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005687.

7. INPUD. In the time of COVID-19: Civil Society Statement on COVID-19 and People Who use Drugs. International Network of People Who Use Drugs. 2020, London, UK. https://www.inpud.net/en/time-covid-19-civil-society-statement-covid-19-…. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

8. Newman K. For Drug Users, COVID-19 Poses Added Dangers. US News and World Report, 2020.Published on-line: https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2020-04-02/c…. Last accessed May 15, 2020

9. The Justice Collaborative. Impact of Covid-19 on our criminal legal and immigrant detention systems. COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Response & Resources. 2020 https://thejusticecollaborative.com/covid19/. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

10. Walter S. Drug rehab shutters amid coronavirus outbreak, sending residents scrambling. Berkeley, CA: The Center for Investigative Reporting. Reveal, May 3, 2020 https://revealnews.org/article/drug-rehab-shutters-amid-coronavirus-outb…. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

11. Wirebeck T. Greensboro alcohol and drug treatment center sidelined by positive COVID-19 tests. Greensboro (NC) News & Record.May 11, 2020.

12. Anonymous. Brainerd drug rehab facility reports COVID-19 case. Brainerd (MN) Dispatch.March 30, 2020.

13. Anonymous. Meeting Guide. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc. https://www.aa.org/pages/en_US/meeting-guide. Published 2020. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

14. Balsamo M. Over 70% of Tested Inmates in Federal Prisons Have COVID-19, Official Figures Show. In. Time Magazine, April 30, 2020.

15. Chappell B. 73% Of Inmates At An Ohio Prison Test Positive For Coronavirus. Washington, DC: NPR, APril 20, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/20/838943211/73-of-inmates-at-an-ohio-prison-test-positive-for-coronavirus.Last acessed May 15, 2020.

16. Reitman J. ‘Something Is Going to Explode’: When Coronavirus Strikes a Prison. In. New York Times Magazine. New York, NY: New York Times; April 18,2020.

17. Navarro M. Yale Study Reports Clean Needle Project Helps Check AIDS. New York Times.August 1, 1991.

18. Kaplan EH, Heimer R. A circulation theory of needle exchange. AIDS. 1994;8:567-574.

19. Kaplan EH, Heimer R. HIV incidence among New Haven needle exchange participants: updated estimates from syringe tracking and testing data. JAIDS. 1995;10:175-176.

20. Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, et al. Counseling plus Buprenorphine–Naloxone Maintenance Therapy for Opioid Dependence. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355::365-374.

21. D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:1636-1644.

22. Madden LM, Farnum SO, Eggert KF, et al. An investigation of an open-access model for scaling up methadone maintenance treatment. Addiction.2018;113:1450-1458.

23. Moore KE, Oberleitner L, Smith KMZ, Maurer K, McKee SA. Feasibility and Effectiveness of Continuing Methadone Maintenance Treatment During Incarceration Compared With Forced Withdrawal. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2018;12:156-162.

24. State of Connecticut Office of Policy and Management; Harteford, CT, 2020. https://portal.ct.gov/OPM/CJ-About/CJ-SAC/SAC-Sites/CJ-Sac/CJ-Sac/Monthly-Indicators/Monthly-Indicators. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

25. New Haven Harm Reduction Working Group. COVID-19 Guidance Harm Reducation_31720.pdf.New Haven, CT:2020. https://yale.app.box.com/v/COVID19HarmReductionGuidance. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

26. Crackdownpod.com. Episode 14: Emergency Measures. https://crackdownpod.com/podcast/episode-14-emergency-measures/2020. Vancouver BC, Canada: British Columbia Centre on Substance Use. Last accessed May 16, 2020.

27. Anonymous. Opioid Treatment Progam (OTP) Guidance. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/otp-guidance-20200316.pdf. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

28. Anonymous. FAQs: Provision of methadone and buprenorphine for the treatment of Opioid Use Disorder in the COVID-19 emergency. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/faqs-for-oud-prescribing-and-dispensing.pdf. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

29. Becker W, Fiellin DA. When epidemics collide: coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and the opioid crisis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020; published on-line, https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-1210.

30. Office of the Governor. Governor Lamont Signs Executive Order Asking Connecticut Businesses and Residents: ‘Stay Safe, Stay Home’. Hartford, CT: The Office of Governor Ned Lamont. March 20, 2020. https://portal.ct.gov/Office-of-the-Governor/News/Press-Releases/2020/03-2020/Governor-Lamont-Signs-Executive-Order-Asking-Connecticut-Businesses-and-Residents-Stay-Safe. Last accessed May 17, 2020.

31. Breen T. Hill Leaders Slam Career Shelter Plan. New Haven Independent.March 19, 2020, 2020. https://www.newhavenindependent.org/index.php/archives/entry/hill_alders_career/. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

32. Cunningham A, Howell B, Feler J, et al. COVID19 Respite Facility for People Experiencing Homelessness. New Haven: City of New Haven, April 1, 2020. https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ForDissemination_DRAFT_March2020_NewHaven_COVIDRESPITE.pdf. Last accessed May 16, 2020.

33. Breen T. Pilot Effort Fails. Who’s To Blame? New Haven Independent.January 28, 2020, 2020. https://www.newhavenindependent.org/index.php/archives/entry/lead_report/. Last accessed May 18, 2020.

34. Joudrey P, Nelson C, Lawson K, et al. Formative Evaluation of the City of New Haven Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) Pilot Program. 2020. https://e1707387-93bc-4dea-b394-4bd7d36f6b59.filesusr.com/ugd/e722b7_20bd8fe976cf4cc0afedf28c5b5fffce.pdf. Last accessed May 20, 2020.

35. McGuire D, Medina M. If CT prisons and jails were a town, they’d have the highest COVID-19 infection rate in the state. Hartford, CT: ACLU Connecticut., 2020 https://www.acluct.org/en/news/if-ct-prisons-and-jails-were-town-theyd-have-highest-covid-19-infection-rate-state. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

36. Lyons K. ACLU files class-action federal lawsuit to lower CT’s prison population during COVID-19. The CT Mirror.April 21, 2020.

37. Brechlin D. Lawsuit that called for reduction of Connecticut prison population over coronavirus concerns dismissed. Hartford Courant.April 25, 2020.

38. Office of the Governor. Governor Lamont Provides Update on Connecticut’s Coronavirus Response Efforts [press release]. Hartford, CT: The Office of Governor Ned Lamont, April 23, 2020. https://portal.ct.gov/Office-of-the-Governor/News/Press-Releases/2020/04-2020/Governor-Lamont-Coronavirus-Update-April-23. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

39. Office of the Governor. Governor Lamont Announces Members of the Reopen Connecticut Advisory Group [press release]. Hartford, CT: The Office of Governor Ned Lamont, April 23, 2020.. https://portal.ct.gov/Office-of-the-Governor/News/Press-Releases/2020/04-2020/Governor-Lamont-Announces-Members-of-the-Reopen-Connecticut-Advisory-Group. Last accessed May 15, 2020.

40. Lyons K. Before mass testing, Department of Correction tested about 6 percent of inmates for COVID-19; of that symptomatic group, almost 83 percent tested positive. The CT Mirror.May 15, 2020.

Figure 1. Details from COVID-19 Informational Brochure for People Who Use Drugs. Developed by the New Haven Harm Reduction Working Group and designed and printed by the Greater Hartford Harm Reduction Coalition.