November is Native American Heritage Month, and Yale School of Nursing (YSN) is featuring Christine Rodriguez, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, MDiv, MA, FNYAM, FAAN, in the faculty spotlight. An ordained minister and family nurse practitioner, Dr. Rodriguez promotes inter-religious understanding and respect for religious spiritual diversity across the lifespan within healthcare settings. At YSN, she serves in the leadership role of Assistant Dean for Simulation and Clinical Innovation.

November is Native American Heritage Month, and Yale School of Nursing (YSN) is featuring Christine Rodriguez, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, MDiv, MA, FNYAM, FAAN, in the faculty spotlight. An ordained minister and family nurse practitioner, Dr. Rodriguez promotes inter-religious understanding and respect for religious spiritual diversity across the lifespan within healthcare settings. At YSN, she serves in the leadership role of Assistant Dean for Simulation and Clinical Innovation.

You’ve mentioned that you have a quote that consistently drives you. Could you share it?

“Da iwakuma’hu le da ixita’hu kena d’ahianiwa le da wawaxi’nei.”

It is a Taino saying that means “My existence is my resistance, and my language is my freedom.”

Can you tell us about your tribal community?

I am a descendant of the Arawak people on both sides of my family. My mother’s ancestry is Garifuna (Honduras), while my father’s ancestry is Taino (Puerto Rico). The Arawak are a group of Indigenous people of northern Southern America and the Caribbean.

As an Afro-Indigenous, Two-Spirit scholar, many will ask about my multi-racial identity. For me, it is important to be connected to a community, where those indigeneity markers related to identity, oral tradition, material culture, customs, agricultural practices, language, spirituality, and genetics are centered in all that we do and are practiced the same way our ancestors practiced them.

As such, while the US does not recognize our sovereignty due to us not being solely US-based, we remain active all across our communities. While our beloved North American relatives celebrate dances differently than we do, it is these 8 indigeneity markers and the respect we have for our community that makes us Native and Indigenous. The consistent fight for our rights amidst the impacts of colonization is what drives us in all our efforts. As such, I am connected to my tribal community. We use the term “yukayeke,” which would be synonymous with “tribe.”

How has your Native American identity informed the way you practice as a clinician?

There are not many of us operating in healthcare spaces or in the higher educational sector. In fact, an article written by Claire Bryan in 2023 in The Seattle Times highlighted this very fact: “Less than 1% of doctoral degrees earned in the US are earned by American Indian or Alaskan Native students, compared with 55% earned by White students.”

The barriers to this are usually structural, as well as cultural in nature. As you can imagine, there is a significant shortage of faculty from this beloved community. As such, I take great pride in being a beacon of hope for my fellow relatives and always representing my indigeneity when someone sees me. When they see one of us succeed, we all succeed.

I remember being told throughout my career that I would not amount to much and college was not a place for me. This fueled me and lit a spark in me, as the search for knowledge coupled with the teachings of my tribal community allowed me to be able to help communities worldwide. My spirituality and holistic practices are centered in everything I do as a clinician.

The integration of the biopsychosocial model, my educational preparation, and lived experiences all drive my connection to ecology, health, equity, spirituality, consciousness, and many other intersections. The overall comprehension of herbal medicines we have used and tinctures we learn to make from our medicine people and our elders truly allow us to provide a more holistic view on healthcare rooted in homeopathy. Moreover, the ability to see things from a dualistic perspective of both masculine and feminine, as well as in between and outside of that binary is rooted in a deep comprehension of the impacts of colonization and how the concept of gender is socially constructed.

What advice would you give to members of the Native American community who are interested in nursing?

Simply do it! I think there exists a great amount of hesitation within the paradoxical nature of colonized vs. decolonized spaces. I certainly struggle each day also, whereby I am embraced by my tribal family and other relatives and then exist in a world that follows socially constructed concepts, such as race, gender, and many others, where at times I feel excluded. Nothing makes me happier than being able to dance in a medicine circle with the various tribal communities across Turtle Island and our beloved world.

My advice is for us to be the bridge that connects these worlds. Similarly to how we bring numerous communities who may not have Native or Indigenous ancestry together for our various intertribal dances during Powwows, we should be doing the same worldwide. One of our Two-Spirit (Biawaisa, our term for Two-Spirit) Chiefs (Kasike’no) , who recently passed had a powerful saying that we continue to uphold as a community: Aban luku, yoba kayuko’no (one people, many canoes). As our people travel in canoes we make, we are aware there are many canoes across various regions… but ultimately, we are one people.

Is there anything else on your mind that you’d like to share?

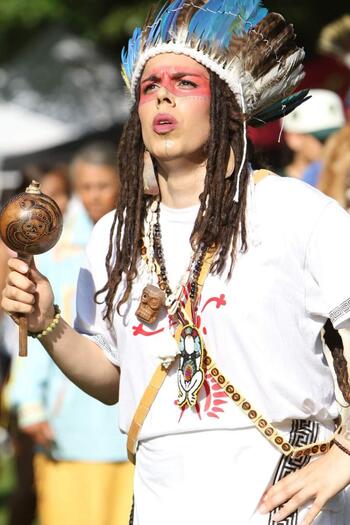

My Indigenous name (Katikaniki) was given to me by our Kasike Atunwa (Principal Chief) and is made up of two words “strong” and “heart.” Together, they make up my name Katikaniki (Strong Heart). While physically my heart is one that does not have a strong rhythm, it is how I carry myself and my commitment to others and my community among many other factors, for why my name was given to me. This same concept is also applied to the headdress (Kaxuxa) we wear, as headdresses are not given to everyone and often are earned due to their powerful significance.

Native American Cultural Center

University resources at Yale include the Native American Cultural Center, which was established in 1993. November events include a beading workshop for graduate and professional school students, a meet-and-greet with Navajo Nation member and Yale College alum Brian Young, and an Indigenous Comedy Night. Interested readers can also sign up for a weekly newsletter.